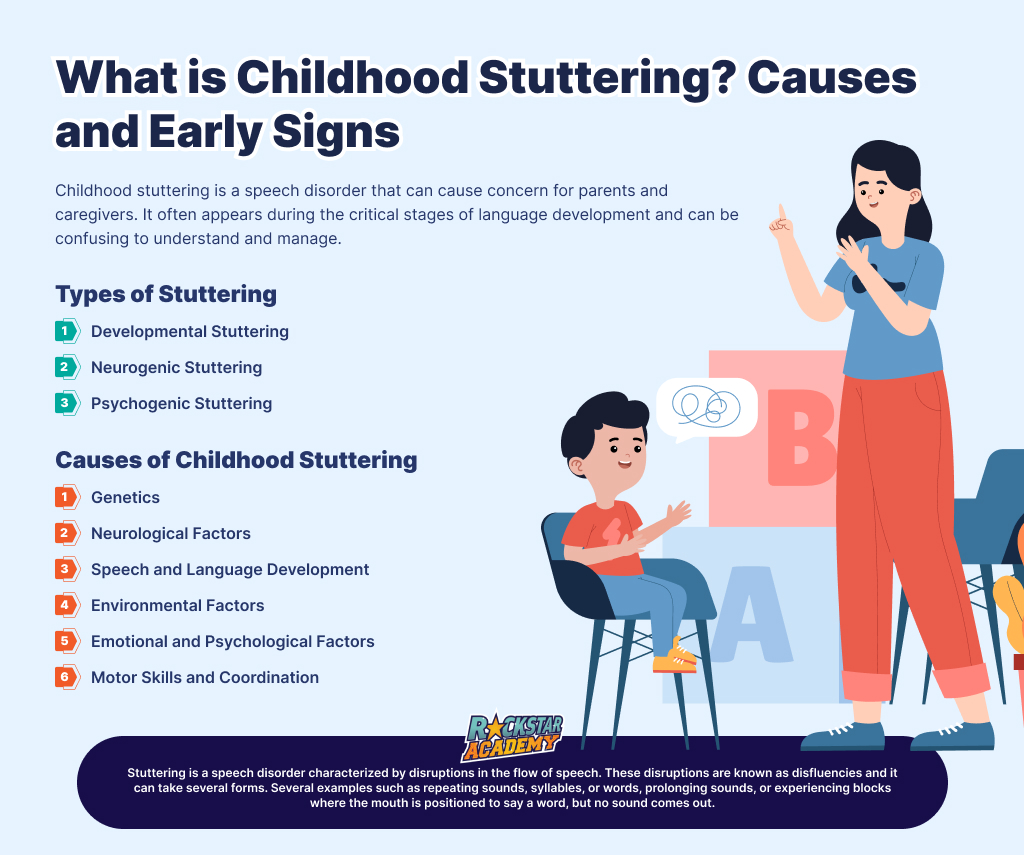

What is Childhood Stuttering? Causes and Early Signs

Childhood stuttering is a speech disorder that can cause concern for parents and caregivers. It often appears during the critical stages of language development and can be confusing to understand and manage.

In this article, we'll explore what stuttering is, its symptoms, the causes, which children are at risk, how it's diagnosed, and what steps can be taken to support a child who stutters.

What is Stuttering?

Stuttering is a speech disorder characterized by disruptions in the flow of speech. These disruptions are known as disfluencies and it can take several forms. Several examples such as repeating sounds, syllables, or words, prolonging sounds, or experiencing blocks where the mouth is positioned to say a word, but no sound comes out.

Stuttering can vary widely in severity, from mild and occasional to more frequent and severe. It's important to note that many young children go through a phase of normal disfluency when they are learning to speak, which is not the same as stuttering. It usually starts between the ages of 2 and 7, when kids are learning to talk more and use longer sentences. This kind of stuttering is also called Childhood-Onset Fluency Disorder.

Childhood-Onset Fluency Disorder is the clinical name for a speech condition where the rhythm and timing of speech don’t match what’s expected for the child’s age. It’s more than just the occasional “um” or pause—it involves things like:

- Repeating sounds, syllables, or whole words

- Stretching out sounds

- Long pauses or blocks before speaking

- Speech that feels effortful or tense

- Repeating short words like “but-but-but”

Children with this disorder may also feel anxious or frustrated about speaking, especially in front of others. That’s why it can affect how comfortable they feel in school or when playing with friends.

It’s actually normal for many young children to have moments of stuttering while they’re learning to speak. But when the stuttering doesn’t go away and starts to make a child feel stressed, embarrassed, or socially withdrawn, that’s when it may be considered a fluency disorder.

This condition is more common in boys than in girls, and it often becomes noticeable by age 6 in around 80–90% of cases.

Types of Stuttering

Stuttering is when someone has trouble speaking smoothly. Words might get stuck, repeated, or stretched out. It’s kind of like a hiccup in your speech. And just like there are different kinds of hiccups, there are different types of stuttering too!

Let’s get to know the 3 main types:

1. Developmental Stuttering

Developmental stuttering is the most common type, especially in young children between the ages of 2 and 5. This type of stuttering usually appears when a child is just starting to put together sentences and express more complex thoughts. At this stage, their brains may be full of ideas, but their speech muscles are still learning how to keep up. That mismatch can lead to stuttering.

For example, a child might repeat sounds or words like, “I-I-I want juice,” or stretch out sounds like, “Mmmmommy, look!” The good news is that developmental stuttering often goes away on its own as the child’s language and speech skills grow stronger. With time, patience, and sometimes a little help from a speech therapist, most kids grow out of it.

2. Neurogenic Stuttering

Neurogenic stuttering happens when there’s been some kind of damage or disruption in the brain, often due to a stroke, head injury, or neurological condition. In this case, the brain has trouble sending the correct signals to the muscles and nerves that control speech. Think of it like a broken wire between your brain and your mouth—the message is there, but it’s not getting delivered smoothly.

Unlike developmental stuttering, neurogenic stuttering usually starts in adulthood and doesn't typically come with the same signs of frustration or emotional struggle. The speech may sound choppy or uneven, and it doesn’t follow a clear pattern. Treatment for neurogenic stuttering often focuses on improving the connection between brain and speech muscles through therapy and rehabilitation.

3. Psychogenic Stuttering

Psychogenic stuttering is quite rare and is usually seen in adults who have experienced emotional trauma or severe stress. This type of stuttering is linked more to psychological or emotional issues than to physical problems with the brain or speech muscles. It can sometimes happen suddenly, especially after a traumatic event, and may also be accompanied by other signs like anxiety, trouble thinking clearly, or difficulty organizing thoughts.

Because it’s tied to mental and emotional health, psychogenic stuttering is often treated with psychological counseling or therapy, rather than traditional speech therapy alone. It’s important for professionals to rule out other causes before confirming this type of stuttering.

Symptoms of Stuttering

Identifying stuttering in children can be challenging, especially since all children have moments of speech disfluency as they develop their language skills. However, stuttering often has specific patterns:

- Repetitions: Repeating sounds, syllables, or words, such as "b-b-b-ball" or "and-and-and."

- Prolongations: Stretching out a sound within a word, like "ssssnake."

- Blocks: A noticeable pause or block where the child seems stuck and no sound comes out.

- Interjections: Adding extra sounds or words into sentences, such as "um" or "uh."

- Tension: Visible tension or struggle in the face, neck, or other parts of the body while speaking.

- Avoidance: The child may start to avoid speaking certain words or in certain situations where they anticipate difficulty.

It's important to recognize that stuttering can vary day-to-day or even within the same conversation. Some children might have more difficulty when they're tired, excited, or stressed.

Which Children are at Risk for Stuttering?

While stuttering can affect any child, certain factors may increase the likelihood of a child developing the disorder:

- Family History

Children with a family history of stuttering or other speech disorders are at a higher risk.

- Gender

Boys are more likely to stutter than girls. In fact, boys are about three to four times more likely to stutter.

- Age of Onset

Stuttering typically begins between the ages of 2 and 6 years. Children who start stuttering after the age of 3.5 years may be more likely to continue stuttering.

- Developmental Delays

Children with other speech or language delays, or developmental delays, may be more prone to stuttering.

- Environmental Factors

High-stress environments or significant life changes can sometimes trigger or exacerbate stuttering in children who are already at risk.

Causes of Childhood Stuttering

Childhood stuttering is a complex speech disorder, and its causes aren't entirely understood. However, researchers have identified several factors that can contribute to the development of stuttering in children. Let’s break down these causes:

1. Genetics

One of the strongest indicators of stuttering is family history. If a child has relatives, particularly parents or siblings, who stutter or have stuttered, they are more likely to stutter as well. This suggests that genetics play a significant role in stuttering.

These genes might influence how a child's brain processes speech and language. For example, some children might inherit a tendency for their speech muscles to have slight timing issues, making fluent speech more difficult.

It’s important to note that not all children with a family history of stuttering will stutter. Genetics is just one piece of the puzzle, and other factors usually come into play.

2. Neurological Factors

Children who stutter may have slight differences in how their brains work compared to children who don’t stutter. These differences are typically found in the areas of the brain responsible for planning and coordinating speech movements.

Speech is a highly complex process that involves many parts of the brain working together. For most people, speech production is smooth because the brain's timing and coordination are in sync. However, in some children who stutter, the brain might not send the right signals at the right time, leading to disruptions in speech.

For example, the brain may have difficulty coordinating the movement of the muscles needed to produce sounds. These timing and coordination issues can cause the child to repeat sounds, prolong words, or experience blocks in speech.

3. Speech and Language Development

Stuttering often emerges during a critical period of speech and language development, typically between the ages of 2 and 6 years. This is when children are learning new words, forming sentences, and experimenting with language.

During this time, a child’s brain is rapidly developing, and they are learning to combine words into sentences, use proper grammar, and communicate more complex ideas. For some children, this rapid development can be overwhelming, and their ability to coordinate speech might not keep up with their expanding language skills.

As they try to say new and longer sentences, the brain might struggle to keep up with the demands of coordinating speech. This can result in the repetitions, prolongations, or blocks that characterize stuttering.

In many cases, this is a normal part of development, and the child will outgrow it. However, for some children, the stuttering persists and requires intervention.

4. Environmental Factors

While stuttering is not caused by external factors like parenting style or the environment alone, these factors can influence the severity and persistence of stuttering in a child who is already predisposed to it.

Environmental factors refer to the child’s surroundings and experiences, including how they interact with family, teachers, and peers. High expectations, fast-paced environments, or significant changes in a child's life (like moving to a new home, the birth of a sibling, or starting school) can sometimes exacerbate stuttering.

5. Emotional and Psychological Factors

Although stuttering is not a psychological disorder, emotions can play a role in how a child experiences and manages stuttering. Children who stutter might become frustrated, embarrassed, or anxious about their speech, which can, in turn, affect their fluency.

If a child is worried about speaking or feels pressure in certain situations (like talking in front of a class or meeting new people), their anxiety might cause them to stutter more. This doesn’t mean that anxiety causes stuttering, but rather that it can make existing stuttering worse.

6. Motor Skills and Coordination

Stuttering may also be linked to a child's motor skills, particularly the fine motor control required for speech. Some children who stutter might have subtle difficulties with the coordination of the muscles involved in speech production, such as the lips, tongue, and vocal cords.

Speaking involves precise timing and coordination of multiple muscles. If a child has difficulty with fine motor control, their speech muscles might not work together smoothly, leading to the disfluencies associated with stuttering.

These motor coordination issues might be mild and not noticeable in other activities, but because speaking requires such precise control, even small difficulties can lead to stuttering.

What to Do About Stuttering in Children

When a child begins to stutter, it can be concerning for parents and caregivers. However, there are many effective strategies and interventions that can help manage and reduce the impact of stuttering. Here’s a comprehensive guide to what you can do:

- Consult a speech-language pathologist (SLP) as soon as you notice stuttering.

- Try speech therapy with a licensed SLP.

- Focus on fluency techniques, stuttering modification, and confidence-building.

- Be patient and give the child time to speak.

- Listen attentively and avoid finishing their sentences.

- Model slow and relaxed speech.

- Encourage, don’t criticize.

- Educate yourself, your child, and others about stuttering.

- Foster empathy and reduce stigma.

- Teach deep breathing and pausing techniques.

- Encourage positive self-talk.

- Use visual or tactile cues for rhythm.

- Listen to the child’s feelings and validate them.

- Focus on the child’s strengths and achievements.

- Show acceptance and love regardless of their speech.

- Schedule regular check-ins with the SLP to track progress.

Need Help in Dealing with Childhood Stuttering?

Recognizing childhood stuttering early and finding effective solutions is crucial for your child's development and confidence. One effective way to address this is by enrolling them in the Preschool & Kindergarten programs at Rockstar Academy.

At Rockstar Academy, your child will benefit from a comprehensive curriculum that includes a variety of physical activities, events, competitions and also includes a focused curriculum for learning phonics. These enriching experiences provide vital opportunities for children to develop academically, socially, and emotionally.

With guidance from our experienced teachers, these programs help children become more adaptive and confident in their abilities. The importance of a well-rounded curriculum cannot be understated, as it is essential for children's overall well-being and success.

Moreover, Rockstar Academy offers a free trial class for those interested in experiencing our programs firsthand. If you want your child to thrive in a supportive and dynamic environment, be sure to contact Rockstar Academy today.

FAQ

Is stuttering just a phase that children will outgrow?

Many young children experience periods of normal disfluency, but persistent stuttering is not just a phase. Early intervention can help improve outcomes.

Can stuttering be cured?

There is no cure for stuttering, but with early intervention and speech therapy, many children can significantly reduce their stuttering or learn effective strategies to manage it.

Does stuttering mean my child has a lower intelligence?

No, stuttering is not related to intelligence. Children who stutter have the same range of intelligence as children who do not stutter.

What should I do if my child starts stuttering?

If you notice persistent stuttering, it's a good idea to consult with a speech-language pathologist for an evaluation. Early intervention can be very beneficial.